Fault Tolerance

Tolerating failures

Distributed systems must be tolerant of a variety of failures. A lot of the failures ecountered in distributed systems reveal themselves as the service being unavailable or slow. They could be network issues, but it could also be a terminating error or garbage collection or some other unplanned behaviour.

Many systems are able to overcome such faults by retrying requests, frequently to another instance of the service. Users can only do this if the other service isn’t suffering from the same disruption as the failed service.

One way that architects can resolve this challenge is by replicating data. When data is replicated, it is assumed to be identical (or similar enough) on other instances that even if the service we were using becomes unavailable, we can stil continue our usage on the replica.

How many replicas should we have?

The number of replicas used highly depends on the replication mechanism. We have already discussed atomic broadcast and consensus algorithms. We will describe a bit more on how they differ with regards to fault tolerance.

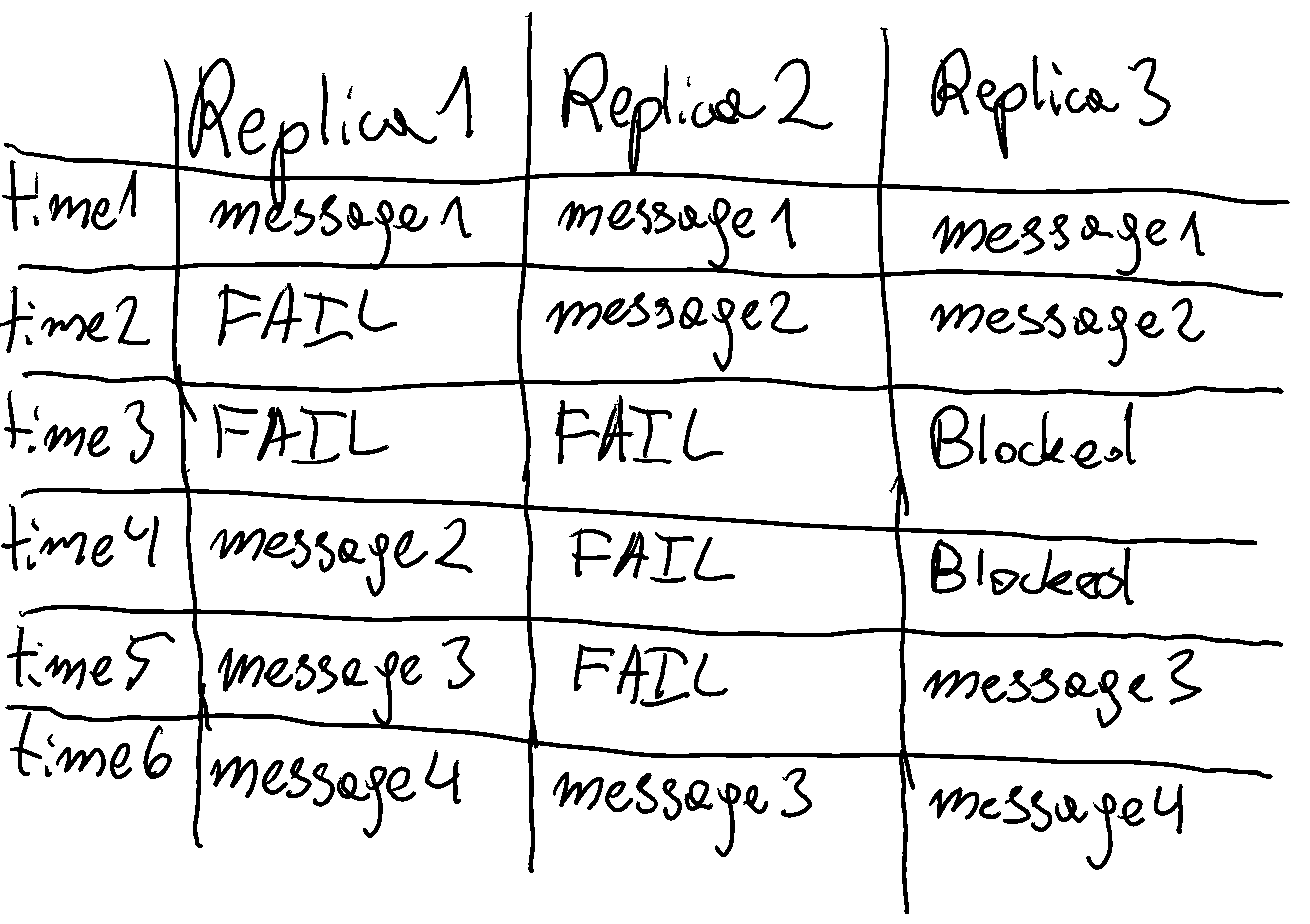

Atomic Broadcast (F + 1)

Atomic Broadcast only transimts information.

The process of transmitting messsages has no reliance on replication - we only care that a message was delivered.

Because we assume all machines have the same messages, we assume that they are already replicated.

Systems using Atomic Broadcast therefore have F + 1 fault tolerance.

This means that if we want to tolerate F failures, we need to have F + 1 instances of the program.

The plus one is the critical server that we need to have any service at all (because it is possible to tolerate 0 failures).

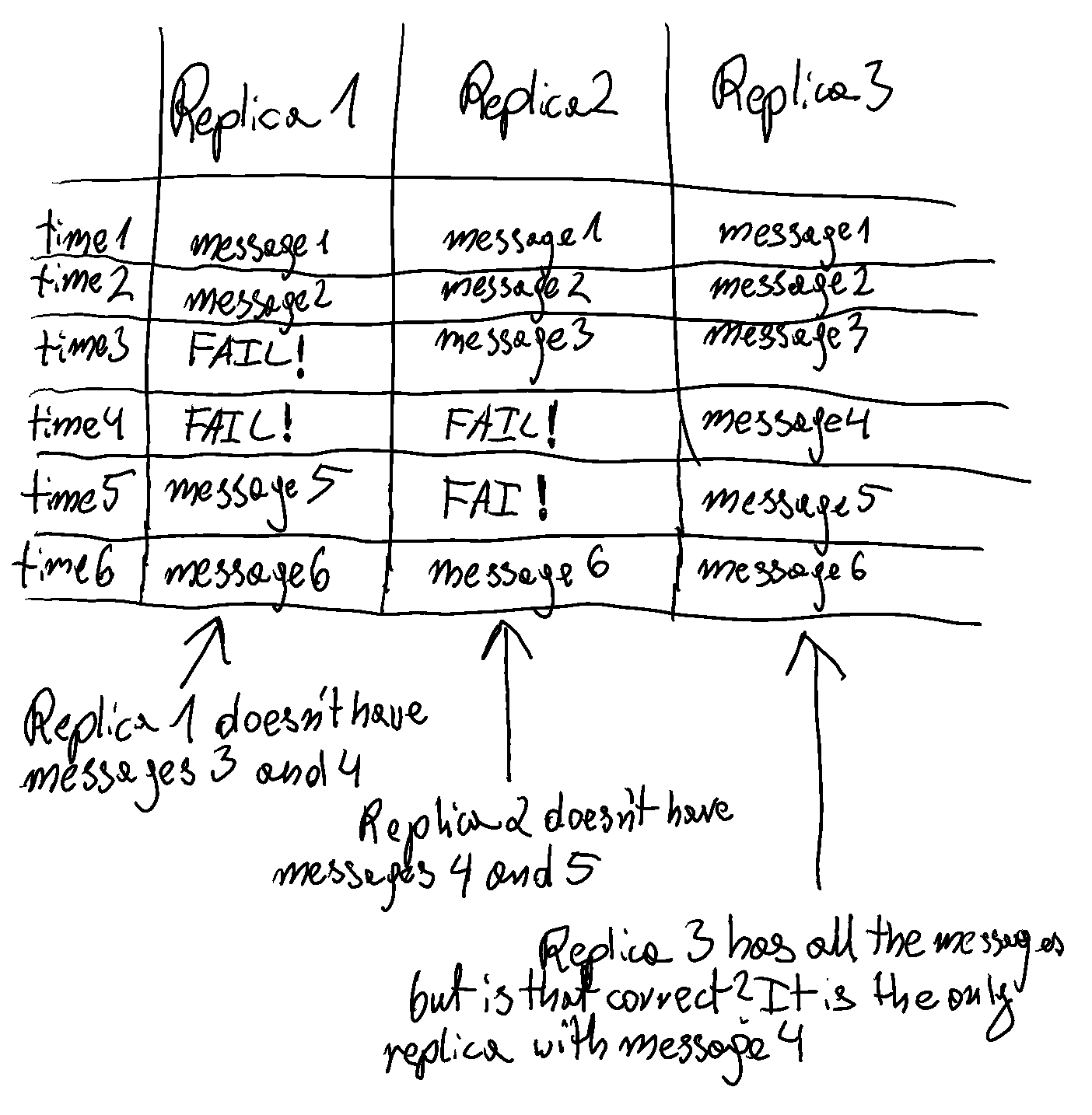

Consensus Algorithms (2F + 1)

Consensus Algorithms are slightly more complicated. These algorithms need to guarantee that all messages are the same on all machines. As such, the algorithms will look at the log of messages sent before making decisions.

The rule is that machines should not acknowledge new messages if they have missed previous messages. Furthermore, consensus algorithms also account for network partitions. This is sometimes referred to as a “split brain” fault, because the symptom is a system split into groups making decisions for themselves. This can happen when for example a new firewall rule prevents 2 datacentres from communicating with eachother.

Without digging too much into the details, the equation used to measure how many machines are required is 2F + 1.

This means that for every failure we would like to tolerate in the system, we need 2 times that, plus one.

The reason for the + 1 in this case is precisely to account for the split brain scenario mentioned earlier.

Without + 1, if the cluster were split into 2 equally sized groups, neither would know for certain if they are in the valid decision making group.

Of course you can have clusters that don’t fit this number, but they act as if they were rounded down to the nearest 2F + 1 model.

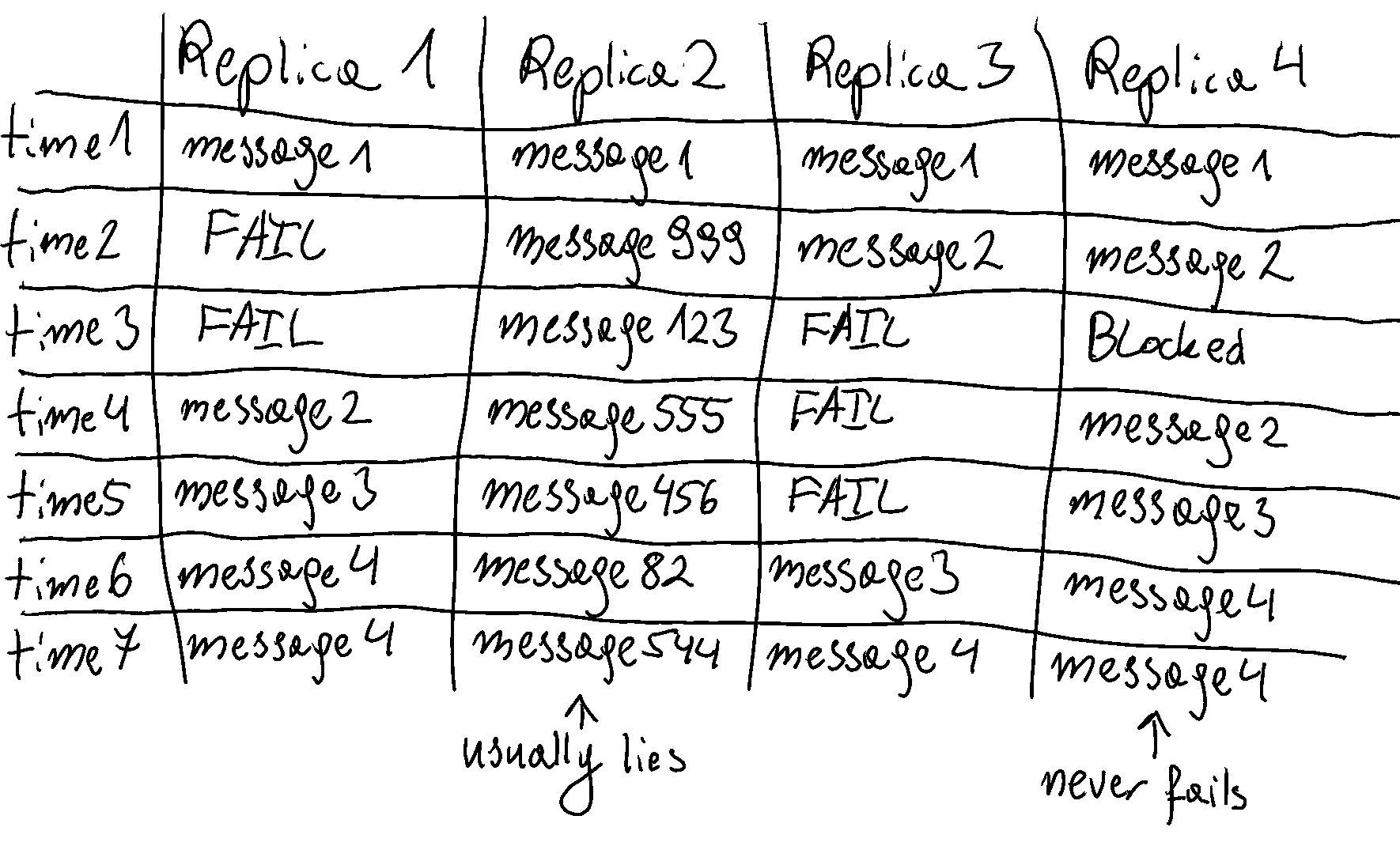

Byzantine Fault Tolerant Consensus Algorithms (3F + 1)

I have posted on Byzantine Fault Tolerance, but will give a brief reminder anyway. A Byzantine Fault is when a replica is lying. It could be proposing new values that aren’t valid, ignoring previous log messages or refusing to cooperate. This is especially tricky to solve, but fortunately it is unlikely to happen in a controlled environment of most organisations. It is however, useful to understand for public Blockchain systems.

The basis for the following equation comes from the paper “Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance”, or PBFT. This is a consensus algorithm that is designed to account for misbehaving replicas.

Similarly to the previous equations, the equation for counting how many machines are required is 3F + 1.

Here, a failure doesn’t matter if it byzantine or not.

If we want to tolerate a single failing replica, we would need 3 times as many programs plus one.

You can reason, that the first group of F machines is for normal failures (such as not responding).

This leaves us with 2F + 1 machines.

If F of the remaining machines are lying, then that means we will have F incorrect messages and F + 1 correct messages.

We can therefore come to the conclusion that while it is expensive to have Byzantine Fault Tolerant systems, they are the safest.

This safety is usually unnecessary for most scenarios.